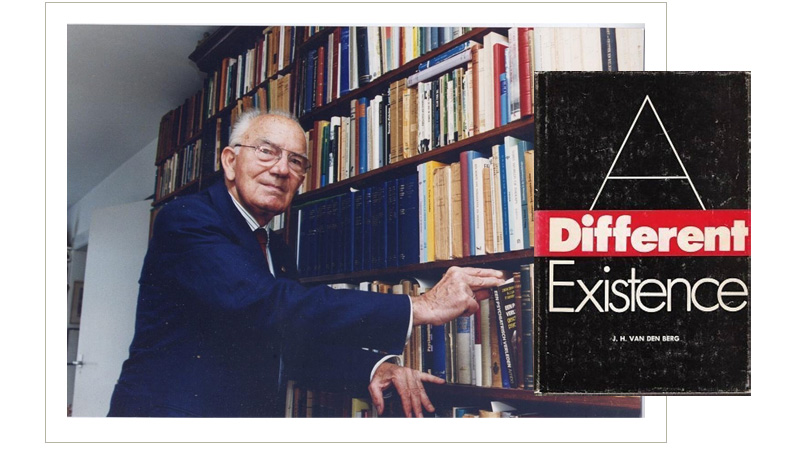

📚 J. H. van den Berg. A Different Existence: Principles of Phenomenological Psychopathology

Пост в телеграме: https://t.me/ironheaded_notes/487

van den Berg, Jan Hendrik.

A Different Existence: Principles of Phenomenological Psychopathology.

— Duquesne University Press, 1972.

“Феноменология!”, — говорят в психиатрии, гештальт и экзистенциальной терапии, в реляционных вариантах психоанализа. Слово произносится, но что это такое, о чем, и чем полезно, понять не так то просто. Сложность в том, чтобы уловить о чем идет речь, но не увязнуть в объяснениях. Объяснения часто или настолько поверхностны и обманчиво понятны, что ничего не дают, или настолько философски нагружены (“начнем с Гуссерля…”), что понять их без дополнительной подготовки невозможно. “A Different Existence” ван ден Берга — объяснение хорошее, вряд ли достаточное, но полезное и вдохновляющее.

Книга построена в основном вокруг разбора одного клинического случая, с отвлечением на другие примеры и теоретические пояснения. И на этом примере показано как можно слушать и понимать жалобы пациента, не перебивая его историю инструментами теории (тут — психоаналитической). Жалобы сгруппированы по четырем категориям опыта: 1) мир (вещей), 2) тело, 3) другие люди, 4) время. Которые психодинамически могут быть объяснены , соответсвенно: 1) проекцией, 2) конверсией, 3) переносом, 4) искажением воспоминаний. На что у автора есть философские и терапевтические возражения. Написано легко и доходчиво.

—

С практической точки зрения феноменология нужна для преодоления привычного взгляда на происходящее. Для этого надо исполнить некий трюк, поворот ума. Феноменологический метод зверь неуловимый, потому что парадоксальный. Чтобы понять себя, вместо того, чтобы заглядывать “внутрь” предлагается смотреть “наружу”, в мир, на вещи. Это призыв перестать выдумывать и вернуться “к самим вещам”, позволить вещам говорить самим за себя. А вещам есть что сказать, как хорошо известно художникам и поэтам. При этом феноменология это не романтический субъективизм, но субъективность весьма дисциплинированная, и поэзия очень конкретная. Поэзия здесь это то, что есть, а не то что кажется. Теоретические и объективные наблюдения сомнительны, а повседневное правдиво и поэтому поэтично (или наоборот). Предлагается отбросить привычку ума разбивать мир на объекты, а потом беспокоиться, не будучи в силах собрать его обратно; перестать задумчиво выбиваться из потока жизни, и отстраненно за ним наблюдать. Не пропускать первый шаг восприятия, удержаться, и до того, как начать выдумывать и сочинять теории — прорваться назад, к тому, о чем мы их выдумываем — к пре-рефлективному смыслу, к прояснению экспериентального, к опыту и его структурам. Психология тогда это наука коммуникативная, описательная, поэтическая, медитативная.

—

Цитаты:

Prereflective life, that is, life as it is lived in our day-to-day existence, has no knowledge of physiology. Eating, one becomes stomach, just as one becomes head, studying — head to such an extent that the hungry stomach does not exist, nor do the tired, crossed legs under the table. In the sexual act, it is not the sexual organs, objects, that are made available to one another, two subjects jailed in their bodies; the mere thought makes the sexual act impossible. In the sexual act, man and woman become creatures of sex, even sexual organs — a change about which the anatomist and the physiologist can establish nothing at all. The matters with which they deal belong to another order, to the order of reflective, therefore, gnostic knowledge, whereas the transformation of the man’s and the woman’s bodies belongs to the order of prereflective, therefore, pathic experience.

So the prereflective body (which we are) certainly has organs — stomach, head, sexual organs, hand, eyes, ear, etc., even blood vessels — but these organs are not identical with those of the books on anatomy and physiology.

The patient of this book is convinced that his heart is diseased. The cardiologist states that there are no defects. His statement makes little impression upon the patient. The reason is obvious, now: physician and patient speak of different organs. The physician is thinking of a hollow muscle, furnished with valves and a septum. The patient speaks of the heart, which can be in the right place; for him, his heart had left the right place. He speaks of the heart that can be broken by a gesture or a glance, whereas the pathologist does not find a trace of a defect. The patient means the heart that can be quite all right even when the cardiologist finds it defective. And which can be diseased even when all physicians declare that it functions splendidly.

To say, then, that the patient “is physically expressing an emotional conflict” is to confuse two realities. He who says that the patient is converting, meaning conveying from one order to another, forgets that the patient is not speaking of the organs meant by the physician, and that he is not converting, not conveying anything from one sphere into another as he keeps speaking within the order of one reality, which he characterized by the fact that the distinction between body and soul has not been made.

The patient does have a diseased heart, he is not mistaken. Neither is he deluding himself; he is suffering from a serious heart condition; for the heart he means is the center of his world. That this center is disturbed, as the patient says, no one can doubt. His heart became cold. Yet not entirely cold. It is rebelling. It is beating restlessly against his chest.

My friend and I are talking to one another. This talking involves talking about something. Just talking, without having a subject to talk about, is impossible. We are talking about Iceland, which neither of us has ever visited, but which we know from the books we read. We are not talking about the image of it created in our minds — this image is a legacy of the objectless subject — but we mean Iceland as it really is. We are talking about a real country. When my friend talks about this country, I try to enter into the things he says; however inaccurate our opinions may be, I try to be in Iceland. When it is my turn to speak, he tries to be with me in Iceland. This being there, together, is our friendship.

[…] I see him, my friend. I see his enthusiastic expression. With my eyes, I go over his face, whose expression harmonizes with that Iceland evoked by him in my mind. In one glance, I see his body, appreciate his look, his smile, his hands. I show my appreciation to him, however vaguely expressed. My appreciation affords him the liberty of speaking as he is speaking, to look as he is looking, and to move as he is moving. My presence is no criticism of his expression but an appreciation of it. In my glance, he can be as he wishes to be. My speaking, hearing and seeing with him and my seeing of his speaking body cause an adhesion between him and his body. This adhesion between him and his body is literally the relationship between him and me: our friendship.

The same applies to me. I am talking about Iceland. I am evoking it with my words, perhaps to the extent that I see it in my mind — yet I have never been there. I do not see an image; my conceptions are reaching the real country, up north. The assumption that these conceptions are aimed at an image and not at reality is, again, the product of a psychology which separates man and world. The image is a sole individual’s possession, whereas this Iceland, reached and visualized through my words, is a possession of ours, my friend’s and mine. That is why I am speaking so easily; that is why I am seeing so much, because my friend is hearing me. I enter this Iceland without compunction, because this friendship with my friend knows no barriers. The removal of the barriers between me and the objects is the friendship between him and me. At the same time, I know he is looking at me. He is seeing me gesticulate, talk, look. I am moving my body freely; without obstruction, I am flowing into my arms, my hands, my throat and mouth, my eyes. I am in possession of my body; I am this body — which implies that I am on good terms with my friend.

It must be admitted that the patient generally follows the preference of his therapist; otherwise, he would not get well. If the therapist is a follower of Jung, the patient has archetypal dreams; with a follower of Sartre, they are existential. The patient learns to know the preference of his therapist; he gets ill in the latter’s preference so that he can get well in this preference. Even the patient suffering from a serious incurable psychiatric disease can, sometimes to a large extent, follow the preference of his physician. Every patient suffers, apart from suffering from his disease as such, from the disease as it exists in the opinion of his physician. He suffers from his physician’s point of view, although this is an odd way to put it. He even suffers from the textbook.

In fact, this is true for all diseases, the purely physical as well, yet it is particularly true for the psychiatric diseases. This fact had, and still has, consequences for the history of psychiatry. Symptoms come into existence and disappear, according to the psychiatrist's historically changing opinion, although almost always an essential element of the disease remains unaltered. This fluctuating of the symptoms with the theory applied is most apparent in neurosis. The symptoms vary from time to time, from country to country, from psychiatrist to psychiatrist, and from opinion to opinion.